Top 10 Easter Russian Foods

Orthodox Easter is one of the biggest Russian religious holidays. As Russians follow the old Julian calendar, they usually celebrate Easter a week later than Protestants or Roman Catholics, who follow the newer Gregorian calendar.

For religious households in Russia, Easter preparations start well in advance – with fasting and cleaning their houses. For them, the holiday begins on Saturday evening, when people gather in dark churches for a collective prayer, waiting for Christ’s Resurrection.

A religious legend has it that it is a day when Jesus put on rags and walked among people asking for food. Since no one knew where they might meet Him, people prepared abundant baskets of food and shared boiled eggs and other Easter staples with the poor. Years ago, there was even a tradition of bringing food to jails to feed inmates and declare that everyone should forgive sinners and show mercy on Easter.

Easter is one of those days when family and friends come together to celebrate life. The table is traditionally covered with white starched tablecloth. The family start eating only after they have lit a candle and placed it in the center of kulich.

Below, we list the most essential Russian Easter foods – starting with symbolical dyed eggs.

1. Krashenki (Russian Easter Eggs)

Dyed eggs are a major symbol of Easter in the Christian world – they stand for Christ’s Resurrection and are the show stopping element of every Easter basket.

Traditionally, Russians would dye hard-boiled eggs a day before Easter, using natural dyes such as onion peels or beetroot, as well as making patterns with parsley and thread. The most skillful grandmas also knew how to dye eggs a bloody red – to symbolize Jesus’ suffering – or create a marble effect with cradle wax.

Nowadays, supermarkets abound in artificial paints and cute stickers that make the experience more straightforward, but real krashenki are still popular.

At Easter breakfast, the eggs are the first to be broken and eaten. In some families, they keep at least one unshelled egg till next Easter – to protect the household from evil. It’s very typical to cut eggs into half and top them with shredded horseradish. Another option is to stuff egg whites with a mixture of mayo and egg yolk pairing them with caviar, similar to how deviled eggs are made.

2. Buzhenina (Easter Ham)

After a lengthy period of fasting, religious Russians enjoy a heavy meat-based Easter table. Traditionally, sausages and hams were cured or brined at home. While one can easily get ready hams at the butcher’s, some housewives prefer fresh, uncured, bone-in ham with a generous layer of fat.

They then brined the meat in water, salt, and flavorings, filling the house with an aroma that tests the patience of the household. They have abstained from meat for the long six weeks of the Great Lent, remember?

Once ready, buzhenina should sit in the fridge for a few days. It is then sliced and served cold on Easter Day.

3. Hren (Beetroot and Horseradish Relish)

This tangy relish enjoys popularity across all Slavic countries. The name itself is slightly confusing in Russian though: hrenis literally means horseradish, which is not the sole ingredient of the dish. The recipe is very basic: grate boiled beetroot and fresh horseradish and mix them together.

They are then left in the fridge for at least 24 hours to marry and become perfect company for buzhenina and boiled eggs. It’s rather a lottery, though, whether your hren will turn out very bitter or not – the root itself may be more or less intense.

Note: There are two things to keep in mind when making this beetroot and horseradish relish. First, always wear disposable gloves – otherwise, you’ll have pink hands for days on end. Second, wear glasses if you don’t want to suffer from watering eyes for hours.

4. Zelts (Russian Head Cheese)

Russian zelts is made from a mixture of lean beef, pork head, and jowls. The meat is cold smoked, cured, and then cooked with lots of spices. It’s important to boil pork skins too – they are responsible for the jelly part.

Although the recipe for zelts is far from appetizing – one stuffs the meat mixture into a bladder or stomach – many people enjoy this cooled and sliced head cheese.

One of its benefits is that it is well preserved and hardly ever goes bad. Zelts is served with hren, mustard, or chopped onions and enjoys popularity regardless of the season.

5. Studen (Russian Pork Aspic)

Another jellied meat – studen (the red meat version) or kholodets (the poultry version) – is cooked across Eastern Europe.

The Russian version is typically studen, made with beef or pork. This dish is rather complicated and time-consuming to put together, but people still make it for every meaningful holiday, including Easter and New Year’s Eve.

One of the reasons for the invested effort is that studen involved using low value meat – there are no leftovers. Another explanation is that making aspic is a perfect way to preserve meat – one can enjoy Easter-designated studen or kholodets a few weeks afterwards.

There is also a fish version of studen, called zalivnoye, but it’s more typically served for New Year’s Eve and winter holidays.

6. Kulebyaka or Coulibiac (Russian Fish Pie)

Coulibiac is a delicious fish dish where salmon is wrapped in puff or short crust pastry. The recipe requires almost as much time to make as a sweet pie would. Well, it is actually a pie, just a savory one.

There are many versions of stuffing: salmon or sturgeon, buckwheat or rice, and dill or parsley. What is never replaced are the hard-boiled eggs, caramelized mushrooms, and onions.

Depending on preference, kulenyaka may be served as a sliced appetizer or a main dish. Alternatively, it can accompany a helping of soup.

7. Yagnenok (Roast Lamb)

If there is a traditional holiday roast, then on the Russian Easter table it’s lamb.

Lamb symbolizes sacrifice and purity – just like Easter itself. Recipes for yagnenok differ from family to family, but it is always baked with an abundance of vegetables and served with a side of mashed potatoes.

Disclaimer: yagnenok is not as big as dyed eggs, kulich, and paskha at Easter. Lots of people replace it with roast duck and chicken or forego roast meat altogether and offer their guests fish instead.

8. Kulich (Sweet Easter Bread)

Kulich has a long history, and its shape has changed overtime – from a long loaf to the contemporary cylinder. This sweetened bread is made with leavened dough and adorned with walnuts and icing. Baking a good kulich requires some time and practice, but its quality is highly symbolic.

Russians say that a delicious, soft kulich signals a thriving year ahead. Kulich can come in various sizes, but it’s important that it be as tall as possible – that’s another signal of prosperity and health for the entire family.

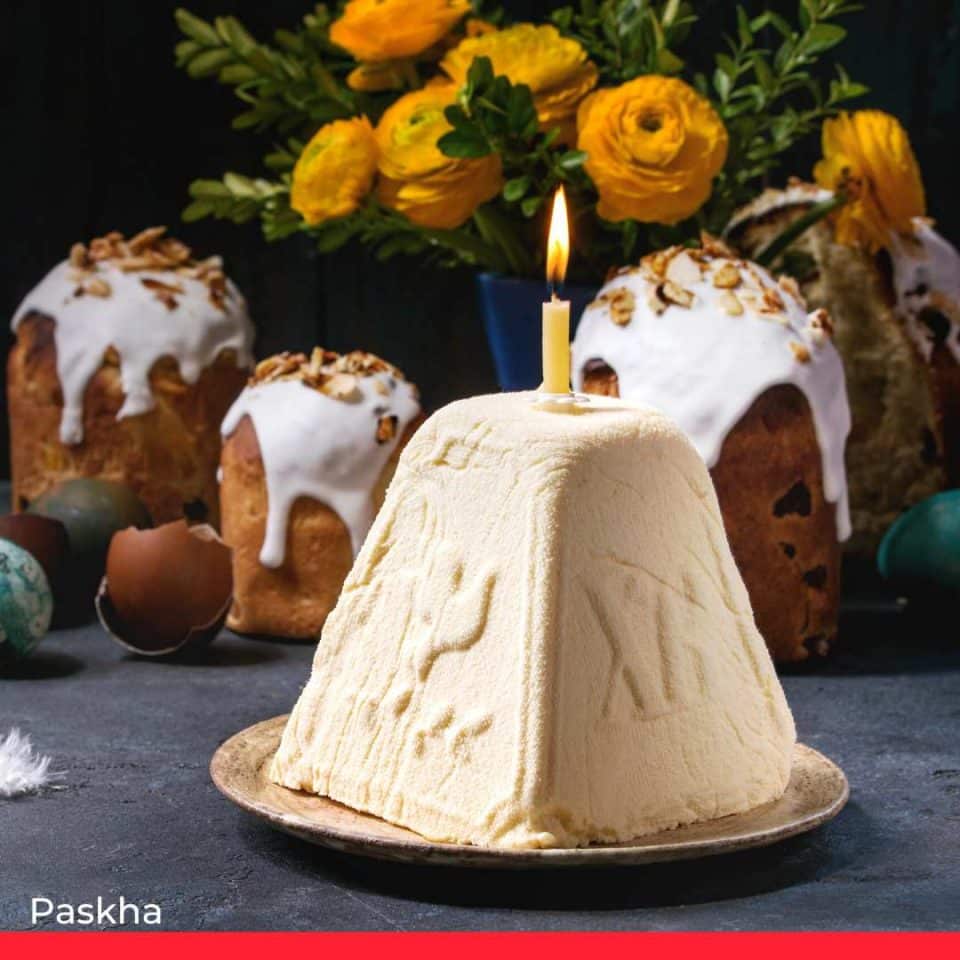

9. Paskha (Sweet Cottage Cheese)

Paskha is a cylinder-shaped, white dessert that symbolizes the purity of Christ. It usually has Christian symbols, such as a cross, molded on its soft texture as decoration.

Paskha contains a sinful amount of butter, sugar, raisins, and nuts and has a creamy texture, reminiscent of something between ice cream and cheesecake. Paskha and kulich are perfect partners in crime: people often use the former as a sweet spread on top of the latter.

10. Makovnik (Poppy Seed Pie)

Russian makovnik is a symbol of prosperity and wealth, and to prove it, one should add as much poppy seed as possible. Makovnik isn’t a lush cake with cream and icing. It’s a one-layer sponge treat where poppies are mixed into the dough.

The secret of making it right is to have 50% flour and 50% poppy seeds. A perfect balance will yield a show stopping, fluffy makovnik that can compete with the fanciest cakes in bakeries.

Russian Easter is not only about meals but about visiting each other and having a glass of wine or vodka and a bite of a blessed egg. The festive table makes up a large part of celebrating this holiday, so be ready to loosen your belt if you visit Russians on Easter Day.

Related: Most Popular Russian Cakes

Related: 25 Most Popular Russian Foods